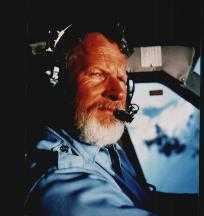

By Sam Wright

I learned to fly in 1964 and have been learning ever since. Started flying commercially in 1965. Spent seven years at a Cessna dealer in So Cal flying Cessna 120's through 310's. This involved instructing and charter. Took a little break first as a non flying GI, then as a small business owner. Returned to flying in 79'. My boss at the Cessna dealer was a former Air Force fighter (F-89) pilot, based in Galena, Alaska. AFter seven years of hearing his Alaska stories, and sometime away from flying, I packed my car and headed North to the land of the midnight sun.I have been in Alaska for the last twenty years with a major break to fly DC-3's in the Eastern US.

I left Alaska looking for a DC-3 job. Thought about puerto Rico so I headed across the US towrad Florida. The weather got so warm by the time I was in Miami, that I doubled back to a more Northern spot. Obtained a position flying freight (mostly at night) in DC-3's and a Beech 18. Currently back in Alaska currently flying De Haviland DHC-3 (Single Otter) on floats and a Cessna 208 on wheels. The city were I work has no roads to anywhere. Because I live sixty miles away, I commute in my own plane on a daily basis.

12907 when I knew her, the info board refers to her as "Miss Piggy"

Another night in the weather

There was only one instrument approach to the small field in Tennessee. On this dark and stormy night I was flying a cargo Douglas DC-3 down the SDF centerline while the co-pilot watched for the runway lights. On the first try we broke out at the MDA directly over the runway threshold, and were too high and fast for a safe landing. A missed approach was in order. The night was black and rainy, no place to be flying around below the ceiling looking for a way down. On this approach we had achieved the MDA almost a mile before the threshold. Breaking out of the clouds at the runway after holding the MDA made us believe that there was a vertical wall of clouds at the approach end of the airport. We needed a plan to land on the next try without busting minimums. There was more than a little turbulence during the next approach. We lowered the gear and flaps at the outer marker and slowed the empty DC-3 to about 75 MPH. This time when the threshold came into view, directly below the nose, I closed the throttles, pulled the props way back and pushed the nose down. The plane fell like a rock and picked up just the little extra speed needed to flare for landing. We made the last turn off with minimum braking and taxied over to the loading aria. We bought some gas and loaded the plane with 76,000 charges for automobile air bags. I read everything I could find on the containers and shipping papers and haz/mat papers, to assure myself that the charges would not ignite as a result of lightning, static charges within the plane or open flame. We departed into the overcast for an explosion free, uneventful night. Reducing the power too far on a Pratt 1830 will produce a very short engine life.

Indigo nite

Sam Wright Flying a Douglas DC 3 with a cargo interior, we were going from Mobil to Indianapolis. We landed in Mobil about 10 PM and loaded some stairs and a flap for a DC 10, these were needed in Indy ASAP. Departed Mobil about 10:45 and climbed on an IFR flight plan to 9,000 feet. The night was moonless with scattered thunderstorms along our route, but we were not in the clouds and could see the lights of the cities below. As the flight continued St. Elmo's fire began to appear on the wing's leading edges and the prop tips. This violet fire continued to grow to a depth of about five inches at the leading edges and the entire prop circle became purple. The frames around the cockpit glass also took on a violet corona. We put our fingers in to the coronas and were able to draw the fire across the glass while serpents tongs of indigo shot back to the frames. I was looking straight ahead when I saw a lightning bolt searching the sky. It seemed to be at our altitude and was aiming to our right and then our left but always moving toward us. The lightning hit square on the DC 3's nose, right at the glide slope antenna. It felt as if the aircraft had hit a watermelon or cantaloupe, just a hollow thump. The brightness of the flash completely blinded me and my copilot. However we did not know we were sightless and thought all the cockpit lights had blown. We each lit our respective flashlights but were still in the dark. This was an immediate concern as we had no auto pilot and some one needed to fly the plane. Slowly my vision returned enough to make out the artificial horizon and keep the wings and nose properly oriented. Soon after this we both could see properly and were amazed by the green glow on each dial and knob. It appears that all the needles and labels in the cockpit were coated with radium, like an old wrist watch. The radium was so old that it never glowed for us before, but the brightness of the lightning recharged the coating. The St. Elmo's fire was gone and all the avionics were in working order and the engines running well so we proceeded toward our destination, which was just 40 minutes away. Five minutes after the strike St. Elmo's fire reappeared. As the intensity of the fire grew we unfolded our sectional charts placing one in each window to block any additional lightning flash. The second strike contacted the right wing tip as reported by my copilot, but I never saw it. Once again we could locate no damage. That was two lightning strikes with in ten minutes. The landing at Indy was uneventful and to this day no lightning damage has been found in the avionics, airframe or engines of this DC 3. PS. The glide slope receiver is still in operation and the flapless DC-10 flew the next day.